On November 20, 1989 the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Rights of the child – a promise to young people to do everything possible to protect and promote their rights to survive and thrive, to learn and grow, and to make children and youth voices heard so they can reach their full potential.

It is critical for the public to understand and recognize that every individual has human rights. Human rights are the globally recognized, foundational elements necessary for living with equality, respect, and dignity. These rights have been enshrined in international law through several human rights treaties developed through the United Nations.

Children and youth have the same human rights as all people, but also have special protections because of their age, limited ability to participate in political processes, and dependence upon adults to make decisions for and about them. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)1 is the treaty that guarantees these special protections to all people under 18 years of age and is the basis for all activities carried out by the Saskatchewan Advocate for Children and Youth.

Canada ratified the UNCRC in 1991, thereby becoming legally obligated to implement it.

The UNCRC recognizes that children require nurturing and guidance as they grow up and that, ideally, this support would come from families and caregivers. However, government – at all levels – has the overarching responsibility for ensuring that the rights of children and youth are respected, protected, and fulfilled.

The rights outlined in the UNCRC fall into three general categories:

• Protection rights – including from all forms of violence, exploitation, and harmful substances.

• Provision rights – including to food, education, the highest attainable standard of health, and an adequate standard of living.

• Participation rights – including to play, have the freedom to access information, participate in matters that affect them, express opinions, and to have their perspectives taken seriously.

Within these categories, the UNCRC provides specific protections and provisions for vulnerable populations, such as Indigenous children or children with disabilities.

There are also three Optional Protocols to the UNCRC that UN Member States can choose to ratify separately. Optional Protocols complement or add to existing treaties by elaborating on an issue in the original treaty, addressing a new or emerging issue, or creating a procedure for the operation and enforcement of the treaty. Canada has ratified two of the three Optional Protocols to the UNCRC – one on the involvement of children in armed conflict, and the other on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. Canada has taken no action on the third Optional Protocol which allows children or their representatives to make a complaint at the international level.

Children’s rights, as human rights, are universal and inalienable. This means that they apply to all children everywhere and should never be taken away, except in very specific circumstances according to due process.

Further, rights are interrelated and interdependent, meaning that, for any right to be fully realized, the others must also be respected.2 For instance, even if a child has access to the highest quality schools, they cannot fully realize their right to education if their nutritional needs are not met and they are too hungry to learn.

There are four guiding principles found in UNCRC articles, which are meant to be a basis for interpreting and assessing the realization of each right and the effective implementation of the UNCRC as a whole:

• Non-discrimination – meaning that the rights of all children must be respected, no matter the child’s race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national, ethnic or social origin, property, disability, birth, or other status. It also means identifying and taking special measures to ensure disadvantaged children can enjoy their rights to the same level as others.

• The best interests of the child – requires that governments systematically consider how children will be affected by decisions, policies, and legislation, and that the best interests of the child is a primary consideration.

• The right to life, survival, and development to the maximum extent possible – refers to the right of children to have measures put in place to not only protect but to facilitate their growth. In this regard, “development” is to be interpreted in a broad and holistic sense, encompassing children’s physical, emotional, spiritual, and psychological development.3

• The right to participation and respect for the views of the child – meaning that children and youth must be given the opportunity, depending on their maturity and ability to form their own views, to be actively involved in all matters that affect them. It obligates us to do more than just let young people speak – it requires decision-makers to take their views seriously.

Despite jurisdictional barriers to incorporation, the Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that international human rights treaties, including the UNCRC, can and should be used to assist in the interpretation and application of legislation that impacts children’s rights in Canada.6 Additionally, it is the most widely ratified international human rights treaty in history. The “near universal” status and global acceptance of the principles and obligations put forward in the UNCRC make it difficult for any level of government to deny

its application.

Nonetheless, because the UNCRC is not embedded within Canadian legislation, there is a common misconception that the standards it sets are “aspirational”, or something to strive for, rather than understood to be required by law. Challenges with enforcement of international laws must be separated from understandings of their actual legal status. The UNCRC is, in fact, legally binding (if not enforceable) within the sphere of international law. Therefore, it must be understood that respecting, protecting, and fulfilling the rights of children and youth is something that governments and all sectors of society are obliged to do – not something they should aspire to do.

Thus, provincial and national human rights institutions, such as the Saskatchewan Advocate for Children and Youth and the Canadian Council of Child and Youth Advocates (of which our office is a member), as well as parliamentary committees such as the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights and civil society, all have a role to play in continuing to advocate for improvements to the implementation of children’s rights and better outcomes for children.

For its part, the Government of Saskatchewan has shown provincial commitment to the UNCRC through its adoption of the Advocate’s Children and Youth First Principles in 2009, which simplify the provisions in the UNCRC to highlight those most relevant to the Saskatchewan context. It is important to note that the first of these Principles broadly recognizes that “all children and youth in Saskatchewan are entitled to […] those rights defined by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.” The province’s adoption of these Principles is significant considering the jurisdictional barriers to incorporating the UNCRC into Canadian legislation. In the words of the then Premier upon adopting these Principles:

Our government is committed to providing children within our province, and specifically those within the care of the Ministry of Social Services with the security and opportunities they rightfully deserve. The well-being of Saskatchewan children and youth is paramount to this government, and as a result, we were pleased to adopt the Children and Youth First Principles.7

The provincial government also stated that, “these principles will act as a guide in examining policy and legislation and in developing and implementing both policy and legislative changes.”8 This action affirms that the provincial government accepts the obligations to respect the rights of children and, therefore, these principles remain a valuable tool for holding the province accountable to its commitment to the children of Saskatchewan.

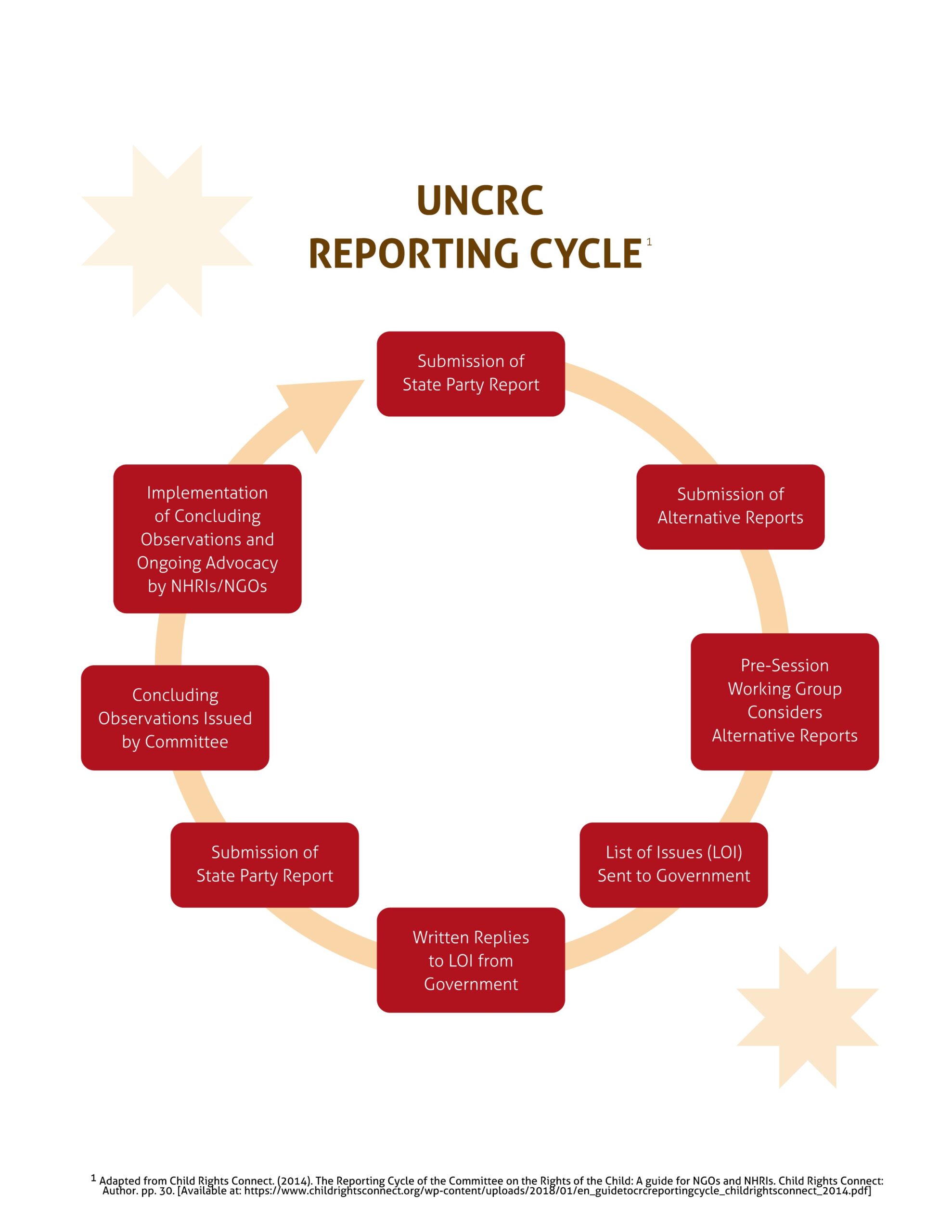

States that have ratified the UNCRC are required to report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (the Committee) every five years on their progress and any challenges encountered.

As part of the review process, non-governmental organizations, individual experts, and National Human Rights Institutions submit Alternative Reports for consideration by the Committee, providing their perspectives on the status of child rights in Canada. This process allows the Committee to develop an independent and objective assessment of a State’s efforts to comply with the UNCRC. The Committee then invites young people and select organizations that submit Alternative Reports to appear at a pre-session meeting, where Committee members ask questions and invite discussion.

After considering all information submitted by both Canada and civil society participants, the Committee may develop a List of Issues for Canada, putting forward areas in which it requires more information. In its response to the Committee’s List of Issues, Canada may collaborate with provincial and territorial governments. Canada would then appear before the Committee in a public meeting.

At the conclusion of the process, the Committee will issue Concluding Observations highlighting the progress achieved by Canada, main areas of concern, and recommendations for improvement. Although non-binding, Concluding Observations are a powerful advocacy tool to press for change which carries significant weight across the globe. The Advocate’s office has frequently referred to previous Concluding Observations from the Committee in its advocacy on children’s rights in Saskatchewan and beyond.

Therefore, advocacy by our office, the Canadian Council of Child and Youth Advocates, and other stakeholders is critical to holding all levels of government accountable for continuing to work towards better outcomes for children and youth. It is crucial to put young people at the centre of all child-serving systems, and making their best interests a priority in all matters that affect them.

Canada’s combined Fifth and Sixth Reports on the Convention on the Rights of the Child are currently under review by the Committee. As is detailed in the following section of this report, our office was able to take on a significant role in this review process in 2020 through its membership in the Canadian Council for Child and Youth Advocates.

Learn more about the UNCRC here